Western

militarism and democratic

control of armed forces*

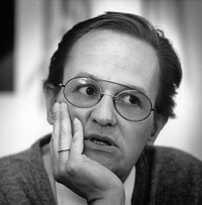

By

Dr.

Jan Oberg, TFF director

"From one point of view

the modern militarist Western society furthers

democratic control; it has become easier since there

is more contact, co-operation, trust and more common

values between those in uniform and those in

three-piece suits. From another angle, war has - in

contrast to what is often stated - become much more

acceptable precisely because of the integration, the

civilianisation-cum-militarisation of the two spheres

of society. And it goes without saying that when

democracies fight wars and make interventions they

know how to legitimate it with reference to highly

civilised norms such as peace, human rights, minority

protection, democracy or freedom - and they do it as a

sacrifice, not out of fear. In contrast, "the others"

start wars for lower motives such as money, territory,

power, drugs, personal gain, because they have less

education, less civil society, less democracy and are

intolerant, lack humanity or are downright

evil."

CONTENT

The need for discussing

democratic control of armed forces

The concept of armed

forces

The blurring of

civil-military relations

Towards an understanding of

post-Cold War, contemporary militarism

Militarism - and unchanged

cultural phenomenon nonetheless:

1) The West itself is

democratic.

2) The West has democratic

control of its armed forces (in a broad

sense).

3) The West knows best, and

it knows how local parties ought to solve their

conflicts.

4) The West has only the

noble motive to promote peace. It is an impartial

Third Party peace-maker or mediator, not a historical

or contemporary party to a local conflict.

5) Thus, the West has a

God-given right to intervene in other people's

conflicts - and not be an object of intervention

itself by anyone.

The needs for

discussing democratic control of armed

forces

One reason we talk about democratic control of armed

forces and not about democratic control of, say, schools

or hospitals may be that armed forces constitute a

special category in social affairs. There are several

reasons for that. They are related to the national and

international interests of the state which in itself is

traditionally defined as the actor that exercise the

monopoly over the tools and methods of violence.

The armed forces are related to the institution of war

and to warfare; but when war occurs, democratic

decision-making is usually more or less suspended. Armed

forces, whether state, para-military or otherwise

non-state, are used to turn over governments in processes

that negate democracy.

In short, there is a problem by nature since the armed

forces are (also) part of society's arsenal of violence

and destruction which, we would like to believe, are

incompatible with democratic governance, with the very

nature of the democratic ethos and operations. This

uneasiness with armed forces can be dealt with, to a

certain extent, by assuming or asserting that armed

forces are there to not be used for which reason

arguments in favour or balance of power, deterrence or ,

in the post-Cold War era, peace-keeping and/or

peace-enforcement.

Another reason for the mentioned unease or perceived

incompatibility between democracy and armed forced is, of

course, that the classical military organisation is

perceived as less than ideal from the viewpoint of

democratic values. Generally, it is centralised and

hierarchical with little opportunity for dialogue and

consensus building and operating under very limited time

constraint, i.e. permitting less dialogue. It is also

much more male- than female. The relationship of armed

forced to secrecy in military and security affairs, to

intelligence and covert operations, to death squads,

clandestine arms and ammunition exports, to human rights

violations and other less noble realities of our world,

make yet another argument for the fact that armed forces

may constitute a problem inside the framework of the open

society that operates according to standard definitions

of democracy.

There are many other reasons for discussing the

possibility of democratic control with armed forces

around the world. If one accepts that there is such a

thing as a military-industrial complex, MIC, (sometimes

extended to include words such as bureaucratic, media,

research) - a concept that has existed since President

Eisenhower's farewell speech - it is difficult to deny

that they can be a fundamental conflict between

democratic society and such complexes as they tend to be

'societies within society' and virtually

unaccountable.

Most democratic societies discuss the allocation to

various sectors on the state budget, but that of national

defence is seldom in focus. World military R&D is, by

far, the largest single research effort; world military

expenditures today equal the combined income of the 49

per cent poorest people on earth, i.e. almost half of

humanity. The leader of the democratic world, the United

States, consumes about 40 per cent of it all, having

recently decided to increase its budget to mind-boggling

328 billion dollars for the year 2002.

Most people, when told, find such figures deplorable

but find, also, that there is little they can do about

changing them. Facts like these speak about wrong

priorities from a humanitarian viewpoint, they speak of

privileges and lack of globally democratic participation

in resource allocation decision-making. They remind us of

the gaps between the haves and have-nots.

In addition, the MIC operates according to principles

that negate the market. Giant, world-wide operating

corporations produce the systems needed by the armed

forces. The state(s) is, normally, the only buyer of

these products, forming what is sometimes called a

monopsonistic market. Competition is minimal, surplus

capital and resources from the civil economy are absorbed

and, when wars are fought, materials objects destroyed.

This combination of surplus capital absorption and

material destruction that call for new investment serves

a balancing, calibrating function in the modern,

globalising market capitalism, not the least in what is

usually called democratic societies.

Finally, there is the huge problem of nuclearism, term

that covers a way of thinking, an ideology and - of

course- the weapons and command structures as well as the

strategies on which they are based. No country or

government possessing them has offered its people a

referendum about their existence or their use in defence

of the domestic territory. The nuclear arsenals which in

the eyes of some promise peace promise and to others

threaten the destruction of humankind several times over

are operated by less than 1000 politicians, technicians

and high-level military world-wide. Nuclear weapons have

been considered fundamentally at odds with the basic

provisions of international law. In spite of all, they

exist, they are developed further - and they are not a

focal point in the debate of democratic societies.

In summary, irrespective of the constructive, peaceful

or humanitarian or other roles armed forces may perform

in democratic societies, there remains a problem given

their very nature as based on violence (whether in use or

not). They exist to be able to perform violent actions.

The relationship of violence versus non-violence to

democracy is curiously under-researched in political

science as well as in social science. Their interaction

with culture and norms - western and non-western - is

likewise neglected; he dominant paradigm of the West

seems, at least for a quick glance, to make such analyses

less relevant or urgent.

The present author tends to deplore this state of

affairs. If a society increasingly base its survival and

development on the interaction between structural and

direct violence (domestic and/or globally), the

hypothesis can be advanced, and merits study, that

democracy in a broad sense will consequently suffer. The

opposite hypothesis also merits further study and

discussion, namely that non-violence, or the minimisation

of violence, will serve to increase democratic sentiments

and governance.

The concept of

armed forces

What is meant by that term today? If by "armed" we

mean organised forces that operate by means of arms, i.e.

violence, there is a quite broad spectrum. First, of

course, there are conscript armies, but they are

vanishing, giving way to professional, more elite-based,

highly professional structures. Then there are popular

liberation armies or movements fighting for collective

purposes against what they perceive as an oppressor.

There are mercenaries, people who fight for whatever

cause as long as they are paid.

There are a variety of categories of para-military

forces, more or less crime or mafia-related, and we have

seen "warlords" operating their own small personal armies

based on loyalty, a sort of post-modern banditry on the

rise world-wide. There is a wealth of Special Forces

which co-function more or less openly with regular armed

forces and are instruments of the state.

Then there is terrorism; it may be defined as the use,

and usually threatening the lives of, innocent people not

party to the conflict at hand to achieve certain

political goals. This definition covers the "private"

terror or terrorist groups that often hit the media front

pages; however, there is a considerably bigger - in terms

of power and people killed - state-based terrorism which

may hold thousands or millions of innocent people as

hostage which less frequently hits those same front

pages.

The sanctions against Iraq is a particularly cruel

example and could also be seen a mass-destructive weapon.

Likewise, the Kwangju massacre in South Korea in 1980

(endorsed by the U.S. State Department), the decade of

sanctions hitting people all over the Balkans and NATO's

(terror) bombing of civil targets in Yugoslavia would

fall in the category of state terror in its consequences,

irrespective of the humanitarian motives that allegedly

legitimated them.

We also find private military companies (PMC)

operating in combined training and advisory roles,

engaged in logistics, military training, base operations,

personal and other security services, Their clients may

be government as well non-governmental forces and they

are frequently the de facto result of "outsourcing" of

operations from defence ministries in, say, the United

Kingdom or the U.S.. In spite of being formally private

and independent of governments, they are staffed by

former military and intelligence officers and promote,

one way or another, the national interests of their

governments. Examples here are Vinnell Corporation,

Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI),

DynCorp, Sandline International, Executive Outcomes,

etc.

The extent to which this type of military corporate

development is compatible with democratic control merits

more debate, particularly since they are usually

'outsourced' - i.e. perform functions with which

governments would rather not be associated in the public

eye.

In summary, when we talk about 'the armed forces'

there is a plethora of types, formations and functions.

The armed forces of democratic states may be seen as more

simple cases and thus more easy to control. However, they

too can be 'tainted' with their more or less direct

relations to and co-operations with less democratic

varieties such as those mentioned above, if not in times

of peace quite often in times of crisis and war.

The blurring of

civil-military relations

There is a number of reasons why, over the last few

decades, it has become increasingly difficult to

distinguish between "the military" and the civilian

spheres of society in modern Western democracies. Here

are some of them, taken from various levels and

spheres:

o The military increasingly takes up civilian

functions from civilian institutions and operators, e.g.

humanitarian catastrophes, humanitarian intervention, and

civil peace-keeping. Add to that transport and general

security including body guards and other protection

measures and special forces in action when, say, heads of

states meet.

o Democratic Western societies have increased the

technical capacity to do surveillance of public space and

bugging all types of communication (Echelon). This is

often done for both industrial and military or

police-related reasons. Democratic states like Norway

have been revealed to collect information on, say,

domestic peace researchers and activists not for spying

in the service of other nations but for having

politically incorrect views on matters of national

defence, security and conflict-resolution. Trends like

these combined with the routine registering of citizens

in an average of 50-100 data bases point in the direction

of control of the people and not by the people; in short,

toward the authoritarian state.

o Technological sophistication is another factor.

Earlier we armed men to make armies, now we man weapons

systems and conduct wars over mind-boggling distances and

swiftly. Complex technology systems require highly

sophisticated expertise, civilian as well as military.

The 'technological soldier' is more likely to wear a

shirt and jeans than a green uniform.

o Much intelligence consist in gathering information

from open sources about civilian affairs and

psychologically important features (PSYOP), not only in

knowing about the opponent's latest weapons systems or

military plans.

o During the 20th century, the proportion of civilians

killed in wars have increased dramatically, modern

warfare aims at a series of civilian targets whether

ethnic cleansing or NATO bombing from the height of 10

kilometres which is bound to increase the probability of

civilian casualties.

o What is with a contemporary buzz word called civil

society - another blurred term - can wage wars more

easily. It costs only a few dollars nowadays to obtain a

Kalashnikov and some radio transmitters; warlords spring

up in war zones and intimidate other civilians in ethnic

cleansing operations. All of it militates against the

more gentleman-like moral code of conduct and concepts of

honour of the classical, professional soldier.

o By consistently covering wars and violence, the

media in general promote, whether intentional or not,

military and other violence-related values and, so to

speak, 'civilianise' them. This coincides with violence

having become an indispensable and quite unchallenged

ingredient in entertainment, particularly movies and

television.

o During the last decade or so, we have also witnessed

an overall weakening of leading, predominantly civilian,

conflict-resolution organisations such as the United

Nations and the Organisation of Security and Co-operation

in Europe, OSCE. The fundamental purposes of the UN to

"save succeeding generations from the scourge of war"

(Preamble) to bring about peace "by peaceful means" and

(Charter Article 1) have been systematically undermined

by leading powers and, by many, considered "unrealistic."

Simultaneously, NATO has emerged as the dominant

peace-keeper (or, at least, conflict-management

instrument) and the European Union (EU) is undergoing a

rapid process of militarisation not the least in the wake

of the handling of the Yugoslav-Kosovo/a conflict in

spite of the fact that it was always know as a civilian

institution.

o A generation of people born in the 1960s and 1970s -

Greens, feminists, leftists and humanists as well as

their NGOs - used to be committed to peace and

non-violence and an alternative, just world order. With

the end of the First Cold War (another could well be in

the making) they have, at least in part, embraced the new

liberal ideology part of which contains a wholehearted

endorsement of conflict-resolution with violent means.

Whatever else may be said about that development and why

it has taken place in the 1990s, it tends to make the use

of armed forces look rather more civil, even civilised,

than less. It also, implicitly, convey a common

understanding that there is a "we" who are civilised and

try to prevent "others" who are a bit more primitive from

fighting each other. It seems, simply, to be the

Zeitgeist in which we live at the beginning of the 21st

century.

Toward an

understanding of post-Cold War, contemporary

militarism

So, the armed forces simply look more civil than

before and, in certain respects, society as such looks

more militant. Once upon a time, social science textbooks

would define militarism or militaristic values along the

lines that the military sought to dominate every corner,

the values and the "culture" and the ways people thought,

thus preparing it mentally for war fighting. Some

advanced the "garrison state" hypothesis while others saw

a "1984" coming.

This is not what contemporary militarism is about;

rather, it is precisely about the organically intertwined

processes of the civilianisation of the military and the

concomitant militarisation of civil society. This

globalising and more "one-dimensional" society (Marcuse)

may, precisely for that reason, have become increasingly

difficult to decipher and, thus, move in the direction of

genuine 'inner' peace and a just world order. And,

indeed, the idea of abolishing weapons and wars - which

could be perceived as one step towards higher levels of

mankind's civilisation - seems pretty much neglected.

Being anti-military was never a useful attitude if for

no other reason because it targeted the person in uniform

rather than the overall system that had produced him. But

anti-militarism could have that focus: against what was

perceived as a dark corner, an authoritarian aberration

or "deformity" built onto society. Take it away, the

pacifist would say, and everything will be fine!

Being anti-military today has to mean a strong

opposition to considerable parts of our Western civil

society and codes which have, over time since 1945 and

the advent of nuclearism, integrated the military in a

increasingly civilian(ised) mode. Popularly speaking, the

military and the rest of society could be clearly

distinguished (and separated) in the past, while in

contemporary society they are much more like Siamese

twins: one can't be changed without changing the

other.

So the armed forces have gained much more legitimacy

in both their military and their (newer) civilian

operations; the price was to become much more modern,

integrated and professional, adopting Western values of

democracy and development rather than remaining in the

barracks with self-isolating authoritarian values of the

classical officer. The soldier has increasingly become a

citizen with a profession like anyone else. He - or she -

is paid to do a job, highly educated, and devoid of the

traditional norms such as patriotism, willingness to die

for a cause, chivalry, honour and paternalism.

Seen in this perspective, it is complete folly to

believe that militarism is incompatible with modernity.

On the contrary, if both spheres so to speak adapt, it is

as manifestly present; it is just much less visible, much

more embedded in the structure of society. Which means

much more difficult to do away with. The soldier no

longer lives outside society at large, he or she swims

like a fish in contemporary Western social formations,

inside our democratic order and norms.

This kind of reasoning can help us explain why, in the

general discourse, humanitarian intervention does not

refer to, say, changes in the direction of a new economy

or world order that would, by political means and human

empathy, create a more just world where everybody would

have their basic needs satisfied. It implies, instead,

that military action is taken within the present order to

protect people who find themselves and their human rights

threatened provided they are also are interesting for one

or the other reason to the interventionist. The

principled altruistic war and wars fought for high

principles whenever violated, is a myth. The defining

criteria is and remains self-interest, state or

corporate, or both. But the policies are not conducted by

generals but, rather, by civilians in suits, academics

and, as in the case of Clinton, Fischer, Solana, Cook,

and other by former sceptics to the military in general

and NATO in particular.

And thus, peace or peace-keeping means the extended,

long-term and/or long-range deployment of forces to keep

levels of violence lower than they would otherwise have

been. It means to try to manage - but not solve - the

conflicts. It seldom, if ever, means doing something

about underlying root causes in all their nasty

complexity or help create a peace that is defined by the

parties themselves. Whatever the United States or NATO

have done, whatever the EU will be doing, with military

means will be legitimated by the stated commitment to

peace. That is anyhow completely non-controversial as no

journalist would ask somebody like Javier Solana what he

means when he talks about peace.

Croatia, Bosnia's two - or rather three units -

Kosovo, Serbia and Macedonia are examples of perpetuated

peacelessness. While the West may have managed to reduce

the direct violence to a certain extent (by introducing

stronger means of violence and not by intellectual force)

, it has not begun to address the structural violence

which is a since qua non of its own global role and

dominance, neither has it begun to address the cultural

dimensions of its own conflict with the local conflict

region in the past and the present.

In summary, from one point of view the modern

militarist western society furthers democratic control;

it has become easier since there is more contact,

co-operation, trust and more common values between those

in uniform and those in three-piece suits. From another

angle, war has - in contrast to what is often stated -

become much more acceptable precisely because of the

integration, the civilianisation-cum-militarisation of

the two spheres of society. And it goes without saying

that when democracies fight wars and make interventions

they know how to legitimate it with reference to highly

civilised norms such as peace, human rights, minority

protection, democracy or freedom - and they do it as a

sacrifice, not out of fear. In contrast, "the others"

start wars for lower motives such as money, territory,

power, drugs, personal gain, because they have less

education, less civil society, less democracy and are

intolerant, lack humanity or are downright evil.

Militarism - an

unchanged cultural phenomenon nonetheless

As this author sees it, there are at least five tacit

assumptions underlying most of the West's

conflict-management policies, particularly as they can be

observed in the Balkans. They can be deduced from

political statements, media coverage and the major part

of the scholarly production. The intellectual's job

should be to bring them to light and raise questions

about them:

1) The West itself is democratic.

2) The West has democratic control of its armed forces

(in a broad sense).

3) The West knows best, and it knows how local parties

ought to solve their conflicts.

4) The West has only the noble motive to promote

peace. It is an impartial Third Party peace-maker or

mediator, not a historical or contemporary party to a

local conflict.

5) Thus, the West has a God-given right to intervene

in other people's conflicts - and not be an object of

intervention itself by anyone.

This means that we are likely to see the West

intervene in are either clearly non-western countries or

countries that are closer to the West but needs

disciplining and then rehabilitation to become truly

western. They are also defined as non-democratic. They

can only be democratised when treated by the western

masters in democracy. Let's now deal a bit with each of

these hypotheses.

(1)

Western democracy, however, means civil

rights, not economic ones. There is very little economic

democracy, no elections held for economic institutions,

be it the corporations or the World Bank, for instance.

If the world is democratising, it is in the sense of more

and more countries adopting the western democratic

institutions such as elections in multiparty systems for

parliaments. That these institutions in, say,

former-Communist countries are fraught with the abuse of

power, election rigging, authoritarian rule,

mafia-connections etc. is indisputable but deferred to

the category of "transition" problems, i.e. everything

will eventually be fine. In the republics of former

Yugoslav republics we now see a concentration of powers

in the same hand which used to be on different hands:

politics, media, military and economy.

In the West itself, the leading country now selects

rather than elects its President (George W. Bush) and

mass demonstrations and dissatisfaction is on the

increase in western summit cities because citizens feel

powerless vis-a-vis increasingly super-national

decision-making in ever bigger units. There is a constant

talk about a democratic deficit. Anyone acquainted with

power games knows that the most important power is to set

the agenda, not just discuss its various items.

Citizens in Europe increasingly voice the opinion that

it does not meet the essence of democracy to be permitted

now and then to vote 'yes' or 'no' to one issue

formulated by the powers that be. They, quite correctly,

see democracy as defined by common, participatory agenda

setting, consensus building and dialogue and a process

involving more than one as well as being built from the

ground up. In short, they want choice and not just to

vote. They want reversibility and not to be told that

they must vote now and what they vote for, such a

membership of this or that organisation, can't be changed

once they have done it.

The era we live in is characterised by what it

succeeded but not what it is: we call it the post-Cold

War period. Be this as it may, two major trend-setters

(and conversation pieces at scholarly conferences) are

Fukujama's about the "end of ideology" and Huntington's

about the "clash of civilisation." The first helped

legitimise the reduction of pluralism and produce the

prevailing sentiment that there is only one way to

conceive of and do things: only one notion of human

rights, of democracy, of peace-making, of economic

development, and of organising the world, namely the

dominant paradigm of the West. The other, whether

intended or not, solidified a sense of western

triumphalism over its major challenger throughout the

20th century as well as produced a (non-existent)

civilisational threat against that very West. Instead of

being descriptive, both curiously turn out to be

prescriptive. (And anything but intellectually impressive

products).

(2) When

it comes to Western handling the last decade or so of

other people's conflicts, the Balkans remain a towering

example of fiasco, i.e. if the original noble intention

were to help the 23 million people who wanted something

else but Tito's Yugoslavia.

With regard to the theme of this analysis, it is

becoming increasingly clear that the international

'community' - a term which should be used only about the

UN but could be said in reality to stand for less than a

dozen western leaders - has had not only democratic,

transparent activities in the region.

There has been clandestine arms and ammunition exports

to all sides in contravention of the UN Security Council

resolution prohibiting such transfers to all ex-Yugoslav

republics. The United States was complicit in the

Croatian campaign to drive out the United Nations and

more than 200.000 Serb civilian citizens from Croatia in

1995. This was done by an army that had received much of

its equipment from Germany (former Eastern Germany) and

training by the United States, including MPRI. The

Washington-based firm Ruder Finn masterminded the

propaganda efforts of local allies of the West; private

companies have trained a series of militant actors. At

present the above-mentioned MPRI is known to have trained

KLA/UCK in Kosovo and thus also the NLA in Macedonia

while also serving the Macedonian government. The German

intelligence service BND initially supplied the hardline

Kosovo-Albanians with equipment, later allegedly

substituted by the US Central Intelligence Agency, CIA.

According to German mass media (Hamburger Abendblatt and

Das Erste) sophisticated equipment and 17 Americans were

evacuated from Arachinovo in late June 2001 by NATO in

Macedonia which, as it happens, has no mandate to assist

any side in this conflict on Macedonian territory.

Furthermore, it is a public secret that CIA infiltrated

the OSCE KVM mission in Macedonia in autumn 1998 and that

UN and other missions contained staff who were not always

related to the official purposes of the democratic West

in the Balkans.

Deception, misinformation and PSYOP have been a rather

constant feature of western

conflict-management-cum-warfare. During NATO's bombing a

series of allegations were raised; one was that Belgrade

was behind the killing of the 45 people found in a ditch

in Racak. Later reports on that event have been

classified. There was also constant talk of a Horseshoe

Plan to exterminate all Albanians from Kosovo/a; evidence

was never brought to the public eye. There was a plethora

of figures of people detained, massacred or burnt, but

documented cases so far make up a fraction. And there

were the constant denials of NATO bombing mistakes and

deliberate targeting of civilian facilities.

Later, millions of dollars were transferred from the

West to various groups in Serbia and Montenegro to

promote the overthrow of the authoritarian, but

originally legally elected, regime of Slobodan Milosevic.

Hardly any western democracy would accept foreign funds

entering its election processes in this manner.

There is more, of course. This will do here to make

the point: democracies would hardly always appreciate to

have their 'Realpolitik' measured with the rod of the

noble motives they profess to have. Indeed, they are

sometimes completely incompatible with peace. One

question that deserves honest scrutiny is this: to which

extent is can it be said to be true that activities by

democratic governments are actually the outcome of

democratic decision-making or, if at all, the will of the

people? To put it crudely: to which extent would citizens

in western democracies endorse policies and activities

like those mentioned above if they were properly informed

about them and given a chance to discuss them? Would they

see them as compatible with a democratic ethos and, if

so, how and why?

But this pertains only to the direct dimension; there

is also an indirect one: western democracies seek to

promote democracy and convey democratic values in

conflict zones. One reasonable question here is, what

means can be selected and which should be avoided in the

struggle to convince somebody to adopt our democratic

values? In short, what can meaningfully be said, in the

sphere of international (power) politics, about the

classical means-end problem?

(3)

Next, the West seems to know what is best for the locals.

While it is truly good to help local conflicting parties

to stop using violence and establish a cease fire, this

in and of itself should not constitute a license to also

force them to accept foreign-manufactured peace plans,

constitutions, institutions, economic or financial

policies. The process of creating sustainable peace

requires completely different competence, education,

training and a different organisation from that of

producing a cease fire agreement. The "audiences" are

also different; a cease-fire is usually agreed among a

few top political and military leaders. By definition,

peace, normalisation, new social, political and economic

development, reconciliation and perhaps even forgiveness

are deeply human, civilian and individual as well as

collective processes. To be sustainable they require a

dogged, long-term engagement by a multitude of parties

and experts and not predominantly top-down but from the

bottom-up. There is no quick-fix peace.

Most small group mediation and democratic legal

processes are conducted by professionally trained

experts, e.g. psychologists and lawyers. But it is a

conspicuous fact that none of the main mediators and

other conflict-managing diplomats who have been engaged

in, say, the Balkans since 1990 have such professional

training. They are not known to have as much as a

one-week training course, let alone a background in

academic peace and conflict-resolution, to back up their

efforts. This does not imply that only professionally

trained "experts" can succeed in mediation; one can also

be a great artist without having a diploma from an art

school. But it might help reduce the risk of failure.

As is well known from mediation in smaller groups, an

agreement will not hold and nothing will work if the

parties do not take active part in the process and

experience ownership in the negotiated outcome. But

simple knowledge like this is completely ignored in

international conflict-management and the international

"community's" practices. This is one reason why so-called

peace plans such as Dayton for Bosnia-Hercegovina, Erdut

for Eastern Slavonia in Croatia, UNSC Resolution 1244 for

Kosovo/a and - recently the EU efforts to manage the

conflict in Macedonia (as of end of June 2001) - have

produced more peace processes than genuine peace.

Conflict-resolution and -transformation processes are

dependent on the quality of causal analysis, of

diagnosis, of the complex of conflicts underlying the

violence. Conceptualisations which assumes that conflicts

have basically two parties, that the conflict is located

in one (the bad) and not in the structure, the

relationship, the situation or the history, and that

conflicts can be solved by only punishing the bad side

and rewarding the good side, are simplifications. They

are bound to lead to conflict-mismanagement and

peace-prevention. Unfortunately they are typical for the

self-appointed mediating and peace-making West. Combine

that with western missionary zeal and the wish to spread

western values, multiparty systems, market economy, and

NATO expansion etc - and you have a fairly dangerous

mixture.

(4) It

can safely be assumed that sentiments and domain

assumptions such as those of Fukujama and Huntington help

permit the West to be seminally ignorant about the right

to democratic decision-making in newly sovereign states.

It pertains to all the countries in Eastern Europe.

Macedonia, for instance, suffered from western

sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to

the point of economic collapse and mafia-isation. Then

its air space was violated by NATO and its territory

'made available' to the Extraction Force. Then the

UNPREDEP mission was forced to leave a week before NATO's

bombing after a unique diplomatic charade involving a

billion dollar promise and recognition of Taiwan. Then

the country was converted into a combined refugee camp

and military base. Since then it has become the object of

western-trained and -supported Albanian extremist

(NLA/ONA/UCK) activity out of KFOR- and UNMIK-governed

Kosovo releasing de facto (low-intensity, so far) war in

what was originally termed the the only'oasis of peace'

in the Balkans.

And in June 2001 NATO's back-up forces in Macedonia

helped 'evacuate' NLA fighters (including allegedly 17

U.S. citizens) from Arachinovo with their heavy,

presumably U.S. and other western, equipment. Writing

this in early July 2001, there is reason to believe that

it is nothing but a prelude to NATO being deployed in the

country.

Is if this was not enough, the country is clearly

being told by western powers that it has no choice but to

join NATO. Its government is also being told by the EU

(Chris Patten) that its counter offensive (what must be

seen as an attempt to defend its territory against

foreign incursion predominantly from Kosovo) is

unacceptable and EU financial support will be withdrawn

since the "money should not be used for bombs." Following

the domain paradigm of the West, the country, its

intellectuals and government alike, do not see any

alternatives whatsoever to NATO membership, EU membership

and more or less shock-therapeutic marketisation of its

economy. So, the Macedonian people might have elections

and can vote, but they have no choice.

The one who believes in the fundamental goodness of

the West and its professed noble motives to help others

live in peace, will hardly look for motives beyond these.

They probably prefer to consider the above "dirty tricks"

as a necessary evil to attain good goals. My ten years as

conflict-analyst on the ground in all parts of former

Yugoslavia tells me that this approach deserves to be

challenged, sooner rather than later.

It's a fundamental mistake to believe that there can

be an isolated view upon or analysis of, say, Bosnia or

Kosovo. What huge and powerful actors decide to do in

small countries (including partitioning bigger ones into

smaller ones) should invariably be seen within a larger,

in this case regional and even global, framework. But the

academic person who, since his or her student days, have

been trained to specialise, focus and stick to one

discipline is likely to miss that point. So too is the

journalist equipped with the task of bringing home a good

'story' with an individual in focus whom we can

sympathise with (victim) or hate collectively (the bad

guys and war criminals). In short it is the task also of

the intellectual to see the difference of what appears to

be (legitimations and official motivations) and what is

(the larger picture and Realpolitik interests).

The other fundamental mistake worth mentioning is that

of distinguishing between an "us" in the West who come in

with no particular interests, serve as impartial

mediators and as what is often (mistakenly) called third

parties, on the one hand and, on the other, a "them" who

are local parties to a conflict and considered less

civilised because they use weapons (often, by the way,

given or sold to them by "us").

I know of no conflict at present in which one or more

western countries have not had serious economic,

political, strategic, resource or other interests and

been historical 'present' in some kind of way. The Danish

journalist Franz von Jessen has written that the Balkans

is the exchange coins used by bigger powers in their

transactions throughout history. He wrote that in 1913

and it makes a precise statement now almost 90 years

later!

For sure the Balkan conflict-management by the West

has been about noble aims, about a wish to stop killing,

ethnic cleansing and support minorities in harms way. But

it has also been about totally different objectives that

demolish its presumed impartiality and fundamental

altruism. Without going into details here, these

objectives have headlines such as (numbers do not

indicate importance):

1. The oil in the Caucasus and transport corridors

North-South and East-West which will pass through the

Balkans.

2. Transformation of NATO to become a 'peace'-keeper

instead of the now marginalised UN and OSCE plus NATO

expansion.

3. Containment of Russia once and for all.

4. Proliferation of market economies and

institutionalisation of western financial institutions

inside each of these economies.

5. An outcome of intra-EU conflict and peddling for

influence, e.g. the spreading of the DM zone.

6. Rivalry about strategic and other interests and

relative strength of the EU and the U.S.

7. The strategically essential triangle involving the

Balkans, the Middle East and the Caucasus - in short the

"Eurasian" dimension of the present and future world

order.

8. The hegemony of the United States and the potential

formation of a new Cold War structure pitting the West

against China and other non-western, ascending

powers.

9. The sophistication of modern military-industrial

interests.

10. The relations, conflicts and mind-boggling

complexities of the interplay of these nine factors.

(5) The

final dimension, the God-given right to intervene.

Unfortunately, top politicians in the US and Europe lack

every willingness to listen. They do not learn lessons,

they teach them. They have too little humility and too

much missionary zeal. They see others as standing on the

lower rungs of the civilisational ladder, themselves (on

its top) as chosen to civilise the savages. Or to make

others their disciples. It's the classical colonial

mind-set: the noble white man's shouldering his burden

while regretting that now and then he needs to use the

sword to make them understand his altruism and

fundamental goodness.

This whole structure is an integral part of western

culture. We can't change it overnight, but we could be

more aware of its influence. It seems to require the

setting up of one set of rules for "them" and another for

"us." Thus, no western country would accept to be an

object of intervention by non-western troops, advisers,

and diplomats. No western country would deliver a citizen

to the Hague War Crimes Tribunal, but they require

governments in the Balkans to do so. Since the Tribunal

has no law enforcer except NATO, no representative or

decision-maker in a NATO country can be indicted for what

looks like war crimes committed during the alliance's

bombing.

Or, how would we feel if four of the UN Security

Council members were Muslim and one a Buddhist country?

What if ASEAN countries or the OAU officially termed

themselves 'the international community'? What if

developing countries put up trade sanctions against the

West, including raw materials, low-wage labour products,

oil, etc and demanded to be compensated for what the West

over centuries has extracted from them?

We are not proposing that this is how it should be. We

are merely raising them as heuristic exercises to

highlight the guidance we can find in Matt. 7:3 to

security and conflict-resolution: be aware of the beam in

your own eye, please!

Buddha expressed it differently: The only thing we

need to kill is the will to kill; we might add the will

to kill other people, other cultures and Nature. The West

has been and remains the main killer globally in this

sense. Someone has jokenly said that the Occident may

turn out to be an Accident!

If we believe in the dynamism of the West, there is

also hope that it does not have to be like that. Gandhi

was once asked what he thought about western civilisation

and answered with a smile that it would be a good idea.

All it would take is Matt. 7:3 and a fundamental

recognition of this plädoyer for pluralism and

cultural nonviolence, formulated by Gandhi and nailed on

the wall of his Sabarmati ashram in Ahmedabad:

"I do not want my house to be walled in on

all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the

cultures of all lands to be blown about my house as

freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my

feet by any."

What better recipe for global tolerance and local and

global peace, for multi-culturally respectful

conflict-management? What better guideline to a

globalising world? What better philosophy to preserve

pluralism and unity in diversity?

But, of course, if the West preaches that there is no

alternative to itself , there are only

alternatives.

Jan Oberg

July 4, 2001

*)

Manuscript for the conference "Legal framing

of democratic control of armed forces and the security

sector: norms and realities, " Geneva, May 4-5,

2001-07-01. Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of

Armed Forced, DCAF.

©

TFF & the author 2001

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

|