Nuclear

deterrence, missile

defenses and global instability

By

David

Krieger

President, The

Nuclear Age Peace Foundation

TFF associate

Read below

about this pathbreaking new book

with global criticism of the US Ballistic Missile Defence

plans

In the world of nuclear deterrence theory, beliefs are

everything. What the leaders of a country perceive and

believe is far more important than the reality. Nuclear

deterrence is a seemingly simple proposition: Country A

tells country B that if B does X, A will attack it with

nuclear weapons. The theory is that country B will be

deterred from doing X by fear of nuclear attack by

country A. For deterrence to work, the leaders of country

B must also believe that country A has nuclear weapons

and will use them. Nuclear deterrence theory holds that

even if country A might not have nuclear weapons, so long

as the leaders of country B believed that it did they

would be deterred.

The theory goes on to hold that country A can

generally rely upon nuclear deterrence with any country

except one that also has nuclear weapons or one that is

protected by another country with nuclear weapons. If

country B also has nuclear weapons and the leaders of

country A know this, then A, according to theory, will be

deterred from a nuclear attack on country B. This

situation will result in a standoff. The same is true if

country C does not have nuclear weapons, but is under the

"umbrella" of country B that does have nuclear weapons.

Country A will not retaliate against country C for fear

of itself being retaliated against by country B.

Thus, if country A has nuclear weapons and no other

country has nuclear weapons, country A has freedom --

within the limits of its moral code, pressures of public

opinion, and its willingness to flout international

humanitarian law -- to threaten or use nuclear weapons

without fear of retaliation in kind. For a short time the

United States was the only country with nuclear weapons.

It used these weapons twice on a nearly defeated enemy.

Deterrence played no part. The United States never said

to Japan, don't do this or we will attack you with

nuclear weapons. Prior to using the nuclear weapons,

these weapons were a closely guarded secret.

From 1945 to the early 1950s, US strategic thinking

saw free-fall nuclear weapons simply extending

conventional bombing capabilities. The United States

never said that it would attack another country with

nuclear weapons if it did X, but this was implied by the

recognized existence of US nuclear weapons, the

previously demonstrated willingness of the US to use

them, and the continued public testing of these weapons

by the US in the Pacific.

The Dangerous Game

of Deterrence

After the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon

in 1949, the dangerous game of nuclear deterrence began.

Both the US and USSR warned that if attacked by nuclear

weapons, they would retaliate in kind massively. They

also extended their respective so-called nuclear

deterrence "umbrellas" to particular countries within

their orbits. As the arsenals of each country grew, they

developed policies of Mutual Assured Destruction. Each

country had enough weapons to completely destroy the

other. Britain and France also developed nuclear arsenals

because they did not want to rely upon the US nuclear

umbrella, and to try to preserve their status as great

powers. They worried that in a crisis the US might not

come to their aid if it meant that the US risked

annihilation by the USSR for doing so. China also

developed a nuclear arsenal because it felt threatened by

both the US and USSR. Israel, India, Pakistan and South

Africa also developed nuclear arsenals, although South

Africa eventually dismantled its small nuclear

arsenal.

Nuclear deterrence took different shapes with

different countries. The US and USSR relied upon massive

retaliation from their large arsenals of tens of

thousands of nuclear weapons. The UK, France and China

maintained smaller deterrent forces of a few hundred

nuclear weapons each. India and Pakistan tested nuclear

weapons and missile delivery systems, but it is uncertain

whether they have yet deployed nuclear weapons. Israel,

known to have some 200 nuclear weapons, offers only the

ambiguous official statement that it will not be the

first to introduce nuclear weapons into the Middle

East.

One obvious way that nuclear deterrence could fail is

if one side could destroy the other side's nuclear forces

in a first strike. To prevent this from happening,

nuclear armed states have tried to make their nuclear

forces invulnerable to being wiped out by a first strike

attack. One way of doing this was to put the weapons

underground, in the air and in the oceans. Many of the

weapons on land were put in hardened silos, while those

in the oceans were put on submarines that were difficult

to locate underwater. For decades the strategic bombers

of the US and USSR carrying nuclear weapons were kept

constantly on alert with many in the air at any given

moment.

Cover of new book from the Nuclear

Age Peace Foundation

edited by the author with Carah Ong

See below

Nuclear deterrence became a game of sorts &endash; a

dangerous and potentially tragic one and also deeply

selfish, irresponsible and lawless, risking all humanity

and the planet. Countries had to protect their deterrence

forces at all costs and not allow themselves to become

vulnerable to a first strike attack on their nuclear

forces. In a strange and perverse way, nuclear-armed

countries became more committed to protecting their

nuclear forces than they were to protecting their

citizens. While they hardened their land-based missile

silos and placed their submarines in the deep oceans,

their citizens remained constantly vulnerable to nuclear

attack.

The game of nuclear deterrence required that no

country become so powerful that it might believe that it

could get away with a first strike attempt. It was this

concern that drove the nuclear arms race between the US

and USSR until the USSR was finally worn down by the

economic burden of the struggle. It also ensured a high

level of hostility between rival nuclear-armed countries,

with great danger of misunderstandings &endash; witness,

for example, the Cuban missile crisis and many other less

well-known scares. Mutual Assured Destruction lacked

credibility, requiring the development of policies of

"Flexible Response," which lowered the nuclear threshold,

encouraged the belief that nuclear weapons could be used

for war-fighting, increased the risk of escalation to

all-out nuclear war, and stimulated more arms racing.

Notice that a first strike doesn't require that one

country actually have the force to overcome its

opponent's nuclear forces. The leaders of the country

only have to believe that it can do so. If the leaders of

country A believe that country B is planning a first

strike attack, country A may decide to initiate a

preemptive strike. If the leaders of country A believe

that the leaders of country B would not initiate a

nuclear attack against them if they did X, then they

might well be tempted to do X. They might be mistaken.

This led to the "launch-on-warning" hair-trigger alert

status between the US and Russia. More than ten years

after the end of the Cold War, each country still has

some 2,250 strategic warheads ready to be fired on a few

moments' notice. Nuclear deterrence operates with high

degrees of uncertainty, and this uncertainty increases,

as does the possibility of irrationality, in times of

crisis.

Ballistic Missile

Defenses

President George W. Bush cites as his primary reason

for wanting a ballistic missile defense system for the US

his lack of faith that nuclear deterrence would work

against so-called "rogue" states. Yet, the uncertainty in

nuclear deterrence increases when ballistic missile

defenses are introduced. If country A believes that it

has a perfect defense against country B, then country B

may also believe that it has lost its deterrent

capability against country A. Ballistic missile defenses,

therefore, will probably trigger new arms races. If

countries A and B each have 500 nuclear warheads capable

of attacking the other, both are likely to believe the

other side will be deterred from an attack. If country A

attempts to introduce a defensive system with 1,000

anti-ballistic missile interceptors, country B may

believe that its nuclear-armed ballistic missile force

will be made impotent and decide to increase its arsenal

of deliverable warheads from 500 to 2,000 in order to

restore its deterrent capability in the face of B's 1,000

defensive interceptors. Or, country B may decide to

attack country A before its defensive force becomes

operational.

If country A plans to introduce a defensive system

with only 100 interceptors, country B might believe that

its nuclear force could still prevail with 500

deliverable nuclear weapons. But country B must also

think that country A's interceptors would give A an

advantage if A decides to launch a first strike attack

against B's nuclear forces. If country A is able to

destroy 400 or more of country B's nuclear weapons, then

A would have enough interceptors (if they all worked

perfectly) to believe that it could block any retaliatory

action by B. Thus, any defensive system introduced by any

country would increase instability and uncertainty in the

system, making deterrence more precarious. Worse, this

introduces a fear that ballistic missile defense has

little to do with defense, and far more to do with an

offensive "shield" behind which a country could believe

that it could coerce the rest of the world with

impunity.

It was concern for the growing instability of nuclear

deterrence to the point where it might break down that

led the US and USSR to agree in 1972 to place limits on

defensive missile forces in the Anti-Ballistic Missile

(ABM) Treaty. In this treaty each side agreed to limit

its defensive forces to no more than two sites of 100

interceptors each. These sites could not provide

protection to the entire country. It is this treaty that

the United States is now seeking to amend or unilaterally

abrogate in order to build a national ballistic missile

defense. It claims this defense is needed to protect

itself against so-called "rogue" states such as North

Korea, Iran or Iraq. At present, however, none of these

countries is even expected to be able to produce nuclear

weapons or a missile delivery system capable of reaching

the United States before 2010 at the earliest

Russia and China have both expressed strong opposition

to the US proceeding with ballistic missile defense

plans. Russia wants to maintain the ABM Treaty for the

reasons the treaty was initially created, and is aghast

at comments from the US such as those of Secretary of

Defense Rumsfeld calling the treaty "ancient history."

Russia is also seeking to reduce the size of its nuclear

arsenal for economic reasons and its leaders fear the

instabilities that a US national ballistic missile

defense system would create. Russian leaders have said

that such a system that abrogated the ABM Treaty could

result in Russia withdrawing from other arms control

treaties including the START II and the Comprehensive

Test Ban Treaty.

China has a nuclear force a fraction of that of Russia

or the US. It has some 400 nuclear weapons, but only some

20 long-range missiles capable of reaching the US. If the

US sets up a system of some 100 to 200 interceptors,

China would have to assume that its nuclear deterrent

capability had been eliminated. Chinese leaders have

called for the US not to go ahead with a ballistic

missile defense system that would force China to develop

a stronger nuclear deterrent force. Were China to do so,

this would inevitably provoke India to expand its nuclear

capability, which in turn would lead Pakistan to do the

same.

Increasing

Instabilities

At a time when major progress toward nuclear

disarmament is possible and even promised by the nuclear

weapons states, the US desire to build a ballistic

missile defense system to protect it against small

nuclear forces is introducing new uncertainties into the

structure of global nuclear deterrence and increasing the

instability in the system. Nuclear deterrence has never

been a stable system. One country's nuclear strategies

have both predictable and unpredictable consequences in

other countries.

Security built upon nuclear arms cannot endure. US

nuclear weapons led to the development of the USSR and UK

nuclear arsenals. These led to the development of the

French and Chinese nuclear forces. The Chinese nuclear

forces led to the development of Indian nuclear forces.

India's nuclear forces led to the development of

Pakistani nuclear forces. Israel decided to develop

nuclear forces to give it a deterrent among hostile

Middle East neighbors. No doubt this provoked Saddam

Hussein &endash; and gave him the pretext &endash; to

develop Iraq's nuclear capability, and is driving Iran to

follow suit.

Now the US is seeking to introduce national and

theater ballistic missile defenses that will provide

further impetus to nuclear arms development and

proliferation. The world is far more complicated than

country A deterring country B by threat of nuclear

retaliation. As more countries develop nuclear arsenals,

more uncertainties enter the system. As more defenses are

set in place, further uncertainties enter the system.

While the US seeks to make itself invulnerable against

threats that do not yet even exist, it is further

destabilizing the existing system of global nuclear

deterrence to the point where it could collapse &endash;

especially when the President demonstrates his belief

that the system can no longer be relied upon.

The full consequences of US missile defense plans are

not predictable. What is predictable is that the

introduction of more effective defenses by the US will

change the system and put greater stress on the global

system of security built upon nuclear deterrence. The

system is already showing signs of strain. With new

uncertainties will come new temptations for a country to

use nuclear forces before they are used against it.

Nuclear deterrence is not sustainable in the long run,

and we simply don't know what stresses or combination of

perceptions and/or misperceptions might make it fail.

Nuclear deterrence cannot guarantee security. It

undermines it. The only possibility of security from

nuclear attack lies in the elimination of nuclear weapons

as has already been agreed to in the Non-Proliferation

Treaty and reiterated in the 2000 Review Conference of

that treaty. Ballistic missile defenses, which increase

instability, move the world in the wrong direction. For

its own security, the US should abandon its plans to

deploy ballistic missile defenses that would abrogate the

Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, and instead provide

leadership in immediately negotiating a Nuclear Weapons

Convention leading to the phased and verifiable

elimination of all nuclear weapons, like the

widely-acclaimed enforceable global treaty banning

chemical weapons.

David Krieger is

president of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. He can be

contacted at dkrieger@napf.org.

More articles by him and information on this subject

can be found at www.wagingpeace.org.

The author would like to thank Commander Robert Green

for his helpful suggestions on this paper.

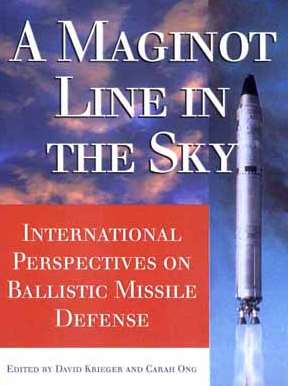

A Maginot Line in

the Sky:

International Perspectives on Ballistic Missile

Defense

Edited by David Krieger and

Carah Ong

$14.95* + S/H fee per copy.

Please call for bulk pricing.

"I think no reasonable person

can read these essays without concluding that the missile

defense project menaces our national security and erodes

our reputation as a global leader."

Richard Falk

J.S.D. Milbank Professor of International Law and

Practice, Princeton University and TFF

associate

This book brings together the views of eighteen

contributors of different nationalities, including

Americans,

on the proposed US Ballistic Missile Defense plans.

These perspectives should be included in any

intelligent

discussion of whether or not the US should proceed

with development and deployment of missile defense

systems.

"This volume is a

treasury of lucid

cogent views which will

enlighten

and inform the decision

makers and

decision molders concerning

aspects

of a missile defense system

which

heretofore have been largely

ignored

and glossed

over."

Rear Admiral Gene R. La Rocque, USN (Ret.), Chairman

Emeritus, Center for Defense Information

Table of Contents

Foreword

Richard Falk

Preface - A Maginot Line in the

Sky

David Krieger

National Missile Defense: Why

Should We Care?

Admiral Eugene Carroll

A Russian Perspective on

American National Missile Defense

Alla Yaroshinskaya

China's Concern Over National

Missile Defense

Dingli Shen

Theater Missile Defense: A

Confidence Destructive Measure in East Asia

Hiro Umebayashi

Missile Defense and the Korean

Peninsula

Samsung Lee

Ballistic Missile Defense:

Consequences for South Asia

Achin Vanaik

Missile Defense: An Indian

Perspective

Rajesh M. Basrur

Ballistic Missile Defense and

Alternatives for the Middle East

Bahig Nassar

Kwajalein Atoll and the New Arms

Race

Nic Maclellan

Canada Is Not Impotent in the

Missile Defense Crisis

Senator Douglas Roche

Ballistic Missile Defense: The

View from the Cheap Seats

Michael Wallace

Pretext for Missile Defense is

Absurd

Sir Joseph Rotblat

Globalization and the New Arms

Race

Andrew Lichterman and Jacqueline Cabasso

Make Missile Defenses Obsolete:

The Case for Ballistic Missile Disarmament

Jurgen Scheffran

We Must Keep Space for

Peace

Bruce K. Gagnon

The National Missile Defense

Mentality in Our Classrooms

Leah Wells

Ballistic Missile Defense: A

Quixotic Quest for Invulnerability

David Krieger

Appendices

A. National Missile Defense Act of 1999, H.R. 4

B. Conclusions of the Commission to Assess the

Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States (The

Rumsfeld Commission)

C. Statement of Russian President Putin on Strategic

Reductions and Preservation of the ABM Treaty

D. Joint Statement of the Prime Minister of Canada and

the President of the Russian Federation on Cooperation in

the Sphere of Strategic Stability

E. Joint Statement by the Presidents of the People's

Republic of China and the Russian Federation on

Anti-Missile Defense

Glossary of Acronyms

Resources

Non-governmental Organization

Contact Information

Authors

How to

order

Nuclear Age Peace Foundation • PMB 121, 1187

Coast Village Rd., Ste. 1 Santa Barbara, CA 93108-2794

USA

Tel: +1 (805) 965-3443 • Fax: +1 (805) 568-0466

• Email: wagingpeace@napf.org

$14.95 each, California Residents please add 7.5%

sales tax. Shipping and Handling (S/H) Fee ($4.00

US/$7.00 International) $

©

TFF & the author 2001

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

|