|

A

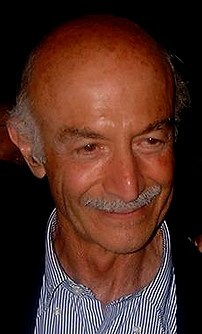

Conversation with Nur Yalman

Nur

Yalman

Professor of Anthropology, Harvard

University

TFF

associate

January 2, 2004 (This interview was conducted in

2001.)

In the fall of 2001, BRC president Masao Yokota met

with Professor Nur Yalman to discuss the root causes of

conflict in the Middle East and long-term solutions for

achieving peace in the wake of the terrorist attacks of

September 11, 2001.

MY: We are now six weeks past the attacks of September

11th. Do you feel the U.S. chose the best option

available when it decided to bomb Afghanistan?

NY: It would have been so much easier not to start

bombing. Instead, we should have brought the Islamic

countries together - all of whom have condemned the

attack - and had them say to the Taliban, "Okay, the time

has come. Get rid of this guy, give him to us, we're

going to try him." That would have been so much easier

than bombing these poor benighted souls. Bombing will get

people very angry. Also, we are really going into very

dangerous waters because we have now destabilized

Pakistan, which has destabilized India. It is also

possible that a very dangerous situation may arise in

Saudi Arabia, and then there will be real trouble,

because Saudi Arabia has oil and money, and India and

Pakistan have nuclear weapons.

MY: You have said elsewhere that no one discusses the

real cause of terrorism. In your view, what is the root

cause?

NY: Daisaku Ikeda [president of Soka Gakkai

International] has been thinking of these matters and

I think his approach has been of great use. His idea of a

dialogue between civilizations, a dialogue between

religions, is a crucial matter. It's obvious to me that

we need to go forward in this direction. We need all our

efforts concentrated on better communication, better

dialogue between civilizations. In that sense, the view

represented by Buddhism is very important.

On the whole, Buddhism has been a very pacific

religion. It is true that there are cases where we had

great trouble with Buddhism - as in Sri Lanka, for

instance - but the message of Buddhism represented by the

Buddha himself is one of making peace between warring

tribes. This is a very good example for the future. My

sense is that we need to continue this effort to bring

people from different backgrounds together so that they

can begin to understand each other.

As for the root cause, I do think the root of the

problem has to do with racism. And the root of racism has

to do with the way countries, including the United

States, have regarded Muslims, in general, and Arabs, in

particular, in the past. That is to say, they have always

considered these people to be second-rate persons. From

World War I onwards, once Britain and France took over

the Arab countries and dominated them, they did not

really consider their interests. And because they did not

consider their interests, they thought that it would be

easy to push the Palestinian people out of Palestine and

give the land to the Jewish people for a national home

for the Jews.

When you look at the historical background, it is

quite clear that Jews and Muslims have existed for

centuries in great peace together all over the Middle

East. The Jews have contributed immensely to the

civilization of Islam: they contributed to music, to the

arts, to literature. Everything gets turned around after

World War II, for it is then that the European problem of

racism - racism against the Jews, anti-Semitism - is

transferred to the Middle East. In effect, the

Palestinian population is made to pay for a European

problem.

How does that happen? There is anti-Semitism in

Germany, in Russia, in Poland, in France, and elsewhere

as well. So the Jews feel uncomfortable. Then they are

attacked by the Nazi forces and so they have to find a

place to escape. Where to escape to? They are given

Palestine, and Israel is created for the Jews.

All of this happens without considering the needs of

the local population. In fact, the local population is

pushed aside. And we now, 50 years later, have the great

problem of two peoples contesting the same piece of land.

We need a resolution of this problem. Without a

resolution of this problem, the relations between the

Islamic world and the rest of the world will not settle

down. This is becoming obvious to all thinking people

everywhere.

MY: So you see European racism as the first issue, the

fundamental root cause?

NY: Yes, that's the first issue, but then there are

other issues which are related to the great anger that

the local populations feel in many Islamic countries

against their own governments. This is true in Egypt and

it seems to be true in Saudi Arabia; there are all sorts

of countries in which the local populations are unhappy

with their governments. This anger takes the form of

feeling dispossessed by the people who support those

governments. And who is it that is supporting those

governments? It's usually the Western powers and

therefore the hostility gets directed to Western powers.

People are well aware that the entire panoply of military

power in the region has been set up for Western

control.

MY: This is the source of violence, even violence

toward the self.

NY: Absolutely, in their acts of desperation, they can

commit suicide. We have seen many people commit suicide

in Palestine. They've been referred to as terrorists, but

you need to understand that these people have been driven

to desperation. We are not taking this seriously enough.

When we first saw all these people committing suicide and

killing a few Israelis in the process, we didn't think

that this was very serious. It was somehow "just a few

terrorists." In fact, it was a symptom of a very profound

malaise that has now come out in the form of this

desperate attack on the Twin Towers in Manhattan. This

is, of course, a totally tragic affair, but not

surprising, given the background of what has been going

on in the Middle East for years.

MY: It is interesting that you see a clear continuum

between the history of trying to solve a problem and

present-day violence.

NY: To return to what I was saying earlier, it all

derives from the fact that people in Europe and the U.S.

do not consider Muslims in the Middle East to be proper

human beings with worries and emotions and rights and

problems. So when we see Palestinian children throwing

stones, people think that it is not so important because

there are so many of them and, so, perhaps they don't

care as much for their children as we do here in the U.S.

But that is never true, because the mothers care for

those children. Yet there is a problem of a magnitude

that is beyond the proper definition of mother-child

relations. It's a terribly tragic situation.

MY: If solutions in the past have led us to this

point, how do we go forward from here with a better, more

long-lasting solution?

NY: Well, we must solve the problems one by one. The

first problem to be solved is really the

Israeli-Palestinian issue. The world must come together

to ensure that there is some just peace established which

protects the rights of the Israelis and protects the

rights of the Palestinians. This is possible. I simply do

not believe that with the immense resources and the

immense intellectual capacity of the Jewish people around

the world, as well as that of the Arabs, that a solution

to this problem cannot be found. It is a matter of people

putting their heads together to try and find a solution

to this problem. It is a problem essentially created by

Europeans and it must be solved with their help. Once

that is solved, then other pieces will fall into

place.

MY: Where does Afghanistan fit in?

NY: I am extremely unhappy that the problem has

migrated to the East. Afghanistan really had nothing to

do with this problem and I'm not sure that they were even

much aware of what was happening in the occupied

territories. But with the arrival of the Arabs in

Afghanistan, things have taken a very nasty turn. And the

development of the Taliban regime has been an unmitigated

disaster for everyone concerned. Once again, we must

acknowledge that Pakistan and the United States have had

a role in that. They were involved in supporting the

Taliban with Saudi Arabia, of course, but in Afghanistan

as well.

MY: And this spills over to other countries in the

region.

NY: Yes. For example, now that the problem has shifted

to the East, it has become embroiled in the Kashmir

issue, which is yet another one of these murderous issues

that needs to be solved, but cannot be solved between

Pakistan and India alone. It will need mediation. It's

possible that Japan can help in that respect as a neutral

power. I think Japan might even be able to help in the

Israeli-Palestinian issue. But obviously all intelligent

people around the world will have to put their heads

together to solve these problems one by one. Otherwise,

we're going to have a very difficult time, not just for

ourselves but also for our children and their

children.

MY: As you remember, in 1993 you kindly hosted BRC

founder Daisaku Ikeda's lecture at Harvard. After that,

he established the BRC to conduct an ongoing dialogue of

civilizations, which he believes is the most effective

way to remove the root cause of conflicts. What do you

think is the best way to conduct a dialogue of

civilizations?

NY: I think what you're doing at the BRC already is

very good, and I think we need to do much more of it. We

need to bring these problems to the attention of world

leaders. We must work with the United Nations. Then we

must bring intelligent people from different places

together to work on these problems.

In the longer term, we need to think of better

governments for spaceship Earth because we're all on the

same spaceship. I have friends - astronomers at Harvard -

who tell me that there aren't very many places in the

universe like ours. We're all on this spaceship, and it's

getting smaller with information technology. This means

we will need to be better governed. And one way in which

we can be better governed is to have more of a sense of

understanding of the needs of other people.

MY: And dialogue provides a mechanism for

understanding...

NY: Yes. In fact, the only way to do that is through

these meetings and discussions and dialogues between

civilizations which Dr. Ikeda has so generously been

supporting. That's absolutely vital. But we need to go

beyond that. We need to begin to think of the systems of

education in different countries. As we all know, Soka

Gakkai's original message has to do with the nature of

education and the significance of education. Once more

we're being made aware of how important this matter

is.

MY: You are referring to education for peace.

NY: Yes, because if you teach hate in schools to large

populations, as apparently is the case with these Islamic

fundamentalist schools all over Asia, this could be very

dangerous. We need to somehow begin to develop a dialogue

with people, with the leaders of these Islamic schools,

which are mainly Saudi-supported Mujahadeen schools.

MY: Does this mean that how young people are educated

in the United States may have to change as well?

NY: Absolutely. I think we need to get a conversation

going on the subject of education, both in the East but

also in the West. Because in the West too, there is a

sense of false complacency. There is too little knowledge

about the nature of Asian society, there's too little

knowledge about Buddhism, too little knowledge about

Hinduism, too little knowledge about Confucianism, and

very doubtful prejudices of long standing about Islam.

These will have to be changed through education.

MY: I was impressed by a statement by Arun Gandhi

right after the September 11th attacks. He said, no one

is born as a terrorist. They are educated to be a

terrorist. Actually, the Taliban are students of a very

extreme way of teaching.

NY: "Taliban" means "student," regrettably.

MY: Transforming our global society through education

will take time. What actions can we take now to change

the course of the current crisis?

NY: The most important practical problem before us

concerns war crimes, war crimes tribunals, and other

tribunals of an international nature, which are

associated with justice. It is absolutely essential that

the U.S. support the International Court of Justice that

was started in Rome. The United States has not wanted to

join that very important initiative of the United

Nations. We must attempt to bring about more respect for

the international rule of law and courts of human

rights.

MY: How would we go about that?

NY: My own preference would be to have a conference, a

serious conference, bringing together all kinds of

lawyers versed in international law and to begin to talk

about regional courts of human rights. We need them

regionally because a court just in New York or just in

Rome or just in Strasbourg is not enough to deal with

problems in Africa, South Africa, East Africa, West

Africa, South Asia, Middle East, etc. We need regional

courts which bring together people from the local

governments in a particular region. And they might go off

to higher courts, but we need to begin to think in terms

of human rights and individuals from different countries

being able to apply to courts of human rights. This is

something very important because it is this sense of

total injustice that drives people absolutely up the

wall. You have that very clearly in the Middle East.

MY: And an international criminal court isn't going to

take care of that? It has to be a regional court?

NY: Yes, it has to be a regional court to which people

can have recourse in their own cultural setting.

MY: Has this idea been tested anywhere in the

world?

NY: A beginning has been made in Southeast Asia. I

gather they have a very elaborate procedure in place now

for dealing with conflict resolution and also human

rights. But we need to begin to think as to how we can

make this into something that is worldwide. I don't know

what the limitations on this would be, but we need to

start thinking about it. The time has come to treat other

people as human beings.

MY: When President Ikeda visited Russia and China in

1975 Buddhist priests asked, "Why do you go where there

are no Buddhists?" And he said, "I go there because there

are human beings." In other words, one of the important

elements of human rights is treating others as human

beings.

NY: Yes. When the Buddha undertook his great

exploration, there were no Buddhists. He was doing it for

humanity, for human beings. And that, in a sense, was

also the message of Muhammad. When he began, there were

tribes with their different idols. One of the critical

moments of Islamic history is when Muhammad breaks the

idols of different tribes to make them understand that

they are all children of the same divine being, that

there is no difference between them, that they're all

human beings. So the message of the unity of human beings

as a whole is part of the original message in Islam, as

well as-of course-of Christianity.

MY: Sometimes people find it easy to say that religion

is a root cause of conflict, and sometimes this seems to

be the reality. But religion also has a very important

role in creating peace in the world because religion

unites people. In your view, what kind of religious

attitude creates conflict and what kind of religion

creates peace?

NY: This is a very profound question, and I'm going to

try to answer it directly. Religion always has two

aspects: one aspect is religious identity, so that you

feel that you're a Buddhist or a Christian or a Jew or a

Hindu or a Muslim or a particular category. That's the

identity function of religion. The identity is tribal,

primitive, barbaric. And all religions have this, whether

we like it or not; they all produce an identity.

The second function of religion is moral and ethical.

And because Of this aspect the great religions are able

to transcend particular identities and produce a desire

for moral and ethical life that rises above particular

religious identities. It is this second element of

religion that we need to bring out, the ethical message,

and it is at that level that dialogue becomes

possible.

The identity aspect is always a hindrance. It is

useful sometimes for people to feel proud of their own

background, but it is a hindrance when you get to the

problem of negotiation and discussion about religious

dialogue. It is at the ethical level over and above the

identity question that real dialogue is possible. The

time has come to overcome our tribalism, to understand we

are human beings. And the only way to do that is to get

out of the identity part of religion to concentrate on

the message.

MY: What you have just said offers hope for the

future.

NY: I think there is a great hope for the future

because it is quite clear that at the ethical level the

messages from the different religions of the world are

very similar to each other, particularly the mystical

elements. In this respect, the great world religions are

very, very similar. Daoism, the Hinduist mystical

elements, the mystical elements in Buddhism, the mystical

elements in Islam, the mystical elements in Shamanism.

They all come very close together in the desire for human

beings to transcend themselves and to become better human

beings, to improve themselves and to rise above their

ordinary, every day existence.

Those desires are very important and in that sense the

mystical teachings in the great world religions - and I'm

not differentiating between Islam or Hinduism or Buddhism

- all celebrate the individual. It is the individual's

own efforts, particularly in Buddhism of course, whereby

you will transcend yourself as a human being and leave

something for the next generation that is better than

what has been achieved before. That great ideal of

bettering humanity, bettering the world, is something

that we need to hope for and achieve.

MY: I agree. Do some religions have a stronger ethical

side than others?

NY: It's a little easier in Buddhism and Hinduism to

see the ethical sides because they are very much

emphasized and the identity side is easier to suppress.

Buddhism and Hinduism both have this very general

humanist aspect to them.

MY: And Confucianism?

NY: And Confucianism and Daoism. And also of course

mysticism in Christianity and mysticism in Judaism and

the Sufi tradition, particularly the Sufi tradition in

Islam. The Sufi tradition is particularly attractive

because it combines this yearning for transcendence,

getting out of one's self, with the idea of the love of

God, but that's just a metaphor for the love of humanity.

This is beautifully expressed by generations of Sufi

poets, the most important of which is our friend Rumi,

who was born in what is today Afghanistan.

MY: Can different religions or cultures learn from

each other?

NY: Japan has a very important role to play because

Japan is non-Western yet highly modern. It, therefore,

can understand the problems of non-Western countries and,

at the same time, lead them in the right direction toward

parliamentary, egalitarian, free societies. What Japan

has been able to achieve is one of the great miracles in

the twentieth century. One hopes that the example of the

Japanese miracle will encourage the intellectuals and

elites in other countries to put in the same effort.

MY: Do you think Turkey might be a parallel to Japan

in that it is a highly modern country that has made a

transition?

NY: Yes. Turkey is the only one of the Islamic states

that has made a successful transition to an open and

vibrant society. It has a long way to go in some

constitutional respects, but it is on the right track,

like Japan. One wishes that Turkey could emulate Japan's

great achievement in educating its population in such a

brilliant way. One cannot but admire the deep sense of

discipline and civic duty so evident in Japan, and so

rare elsewhere. But in Turkey at least you have free

elections, many parties, lots of discussion. The airwaves

are full of excitement. Everybody is willing to talk,

there's free discussion of religion. In that sense,

Turkey is a very good companion to Japan in Asia, and

looks up to Japan as a great example.

MY: Do you see lessons in Japan's experience that

might apply to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict?

NY: Edward Said has written a very interesting article

in which he says the way forward between Israel and

Palestine is that we must have an arrangement to have all

the citizens of Israel and Palestine to have their

individual rights respected as individuals. At the

moment, it's obvious that the Palestinian rights are

nothing. Israel is only thinking of the rights of their

own citizens, and only some of them at that.

MY: Just as Americans only think of their own rights.

Also, some Americans argue that Arab governments have

been shirking their own duties by actually fanning

hostility against Israel.

NY: I think there's no doubt that governments will do

what they think is useful for them. And I must say I have

very little respect for many of these Arab governments

who do not represent their people's interests.

MY: Which we are propping up...

NY: Yes, which the U.S. is propping up. The present

situation, the structuring of the present power in the

modern Middle East, is the creation of the West in one

way or another. Winston Churchill was personally drawing

the borders on the map sitting in a restaurant in

Whitehall in London at the end of World War I. All those

borders were drawn by European powers, by France and

Britain. The whole thing is structured by and for Western

interests.

However, all that aside, each and every one of the

populations in these countries feels very keenly that

they have been scapegoated by Western powers and their

interests are being attacked. This is true of Syria,

which feels that Israel has taken over part of its land.

It's true for Egypt in which the Egyptians feel that

injustice is being done to the Palestinians. It's true

about Jordan and its relations with the West Bank. It's

true in whichever country you deal with. They all feel

that they have been put upon by the Western powers, and I

think they're not far wrong.

MY: Where does this analysis leave Israel?

NY: There is no doubt, given the facts of this

century, that some accommodation has to be made for

Israel's security. Most Arab countries, and I would

venture to say, all the rest of the Islamic countries

would agree to that. If we had a larger international

conference, no doubt there would be an agreement to

provide some safe borders for Israel and make peace. But

if Israel goes on taking over Palestinian land and

creating these settlements on confiscated land that does

not belong to them, you get large Arab populations very

angry, angry at their own governments and certainly angry

at the West, which is maintaining this status quo. Israel

must stop creating situations which engender greater and

greater hostility in the local populations. That creates

ripples that go all the way out to the furthest edges of

Islamic countries and touch many others who recognize

that there's something fundamentally wrong here. It is a

noxious witches' brew which poisons all positive

relations between peoples.

MY: It all comes back to justice, compassion, and

respect for all human beings.

NY: Yes. Regardless of where you begin, that is where

you end up.

(Addendum: Since this interview, the Saudi plan,

adopted at the Beirut summit of Arab States, and

supported by the US, has turned out to be entirely in

accord with the above observations.)

©

TFF & the author 2004

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

|