|

Interview

with S. Srinivasan

- "Vasu" - of Barefoot College

By

Vicky

Rossi

TFF

Associate and Board member

Comments directly to

vickyrossi555@gmail.com

February 16, 2007

Interview

with S. Srinivasan, Facilitator, Barefoot

College, Tilonia, Rajasthan, India. Interviewed in Tilonia inJanuary

2007

The Barefoot

College in Tilonia, Rajasthan, is located on 2 interconnecting campuses.

It has 10 outreach field offices which are instrumental in the coordination

of the activities it carries out in over 150 outlying villages.

The Barefoot campus is entirely powered by solar energy. Barefoot

shares its know-how of solar technology not only with local villagers,

but also with people from other countries like Afghanistan, Bolivia

and Gambia, who visit the campus for a 6 month period during which

they learn how to assemble and repair the necessary solar equipment

in order to bring electricity to their home villages.

In addition

to this important work with solar technology, Barefoot runs night

schools for children who are unable to benefit from mainstream education

because of their family duty to work in the fields or to look after

livestock. Fifty-seven children from these night schools are then

elected as representatives to a Children’s Parliament, which

meets once a month. One child from these 57 is elected as Prime

Minister of the Parliament for a two and a half year period.

Barefoot

is also active in rain water harvesting, weaving and clothe making

as well as in the manufacture of wooden toys for children. It runs

clinics providing medical services based mainly on homeopathic remedies

and it addresses important social issues in the villages through

the performance of puppet shows.

Vicky Rossi: When was the Barefoot College first established and

what was the main motivation of its founders?

S. Srinivasan (commonly known as “Vasu”): The Barefoot College

was founded in 1972 by Mr Bunker Roy and two others. It was a voluntary

organisation specifically formed with the belief that in order to work

with the poorest of the poor in the villages one has to base oneself

in the village. Only in this way can one uncover the problems faced

by the communities there, as perceived by the villagers themselves.

In the initial 1-2 years, the set of objectives held by the organisation

became more concretised and more specific. This led to initiatives being

started with regards drinking water. Access to drinking water was a

problem for the poorest of the poor in the villages and linked to that

was health – access to health services was almost nil.

When the founders of Barefoot progressed

further in their series of village meetings, they realised that although

there were schools, children were not going to them. They discovered

too that there was hardly any employment in the villages that could

sustain the people there, so villagers were migrating to nearby towns

and cities in search of labour. The founders of Barefoot understood

the needs of the community because these needs were spelt out by the

communities themselves. Barefoot College became a fora for urban educated

professionals, graduates and post-graduates to work with the rural youth

in the villages. That’s how it all started.

Vicky Rossi: You have already mentioned a few of the very important

initiatives carried out by the Barefoot College, for example, with

regard to drinking water, night schools and employment opportunities.

Can you indicate some of the many other activities you are involved

with?

Vasu: Well, as I just mentioned, in the beginning, we started tackling

the difficulties faced by the poorest of the poor in terms of access

to drinking water, education, health and livelihood; these were integrated

with one another and the overall objective was to improve the quality

of life in the villages. We found that with regards access to drinking

water people had to go – or rather women had to go – kilometres

away to fetch water. In the same way, they also had to go far to fetch

fuel wood for energy.

There was a myth at the time, which has

been perpetuated, that the poor cannot pay for services. This was something

that the Barefoot College felt that it had to demystify. In the beginning,

when we started installing hand pumps - which we stopped after a few

years because we got involved instead with rainwater harvesting systems

- we realised that we should not duplicate government services, so instead

we mobilise people into becoming aware of which of their perceived needs

can be obtained through their own collective lobbying. When we began

work with rainwater harvesting, we saw the potential for wages for the

community if the local government took up this work, which is labour

intensive, and could therefore provide employment within the villages

so that people there didn’t have to go to the cities.

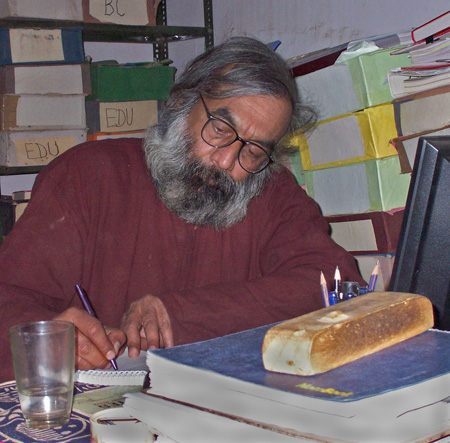

"Vasu"

facilitator of the Barefoot College, India

Copyright © 2007 Vicky Rossi

When the organisation did a survey in 1973 on the state of electrification

in the villages, it was also discovered that there was a great concentration

of artisans i.e. they were doing the survey on the state of electrification,

but they also found out that in the localities there were many weavers

and leather workers. This led to our involvement with artisans.

In the same way when in 1979, a study was

conducted by the organisation into drudgery and its impact on rural

women, we discovered that something like fetching water was considered

drudgery according to the specialists, but for the women themselves

when they went to collect water it was the first and only opportunity

they had to get rid of caste and to talk to one another. So when we

went into the nitty-gritty of it, we saw drudgery from a different perspective

to that normally portrayed by specialists, sociologists and anthropologists.

We saw drudgery according to the rural women themselves and discovered

that because they went to the same place, they had the chance to discuss

their problems e.g. if a woman’s mother-in-law is beating her

up or her sister-in-law is ill-treating her. Fetching water was the

only time and place where they could communicate. When

we did this study, then, we realised that communication was important

and we began to work with traditional methods of communication like

puppet shows and songs.

When we started working with the artisans,

the teachers in the night schools and others, we realised that a lot

of fossil fuels were being burnt by lanterns. We asked ourselves how

we should go about solving this problem because every month people had

to buy kerosene. When solar technology was in its infancy in the early

1980s, there was a young man who worked with the teachers here, who

suggested using solar electricity. That’s how we got started,

in 1984, with solar technology.

Vicky Rossi: Where did you get the know-how for the solar technology

from? Was this man an engineer? What was his name?

Vasu: His name was Chandok. Yes, he was an engineer, but he had never

thought of applying his knowledge in the villages. Then he interacted

with one of the teachers here, who was in charge of the night schools,

and trained him in how to repair and maintain a solar system: understanding

the solar photovoltaic panel, the batteries, etc. After a month or so

the engineer had to leave Tilonia and the teacher was left with the

technology and the proposition of, “How do we go further?”

That’s the position that that teacher was in in 1984 and yet today

he has trained more than 400 women Barefoot solar engineers.

Vicky Rossi: You are saying that the teacher received the knowledge

with regards solar technology from Chandok and then went on to spread

that know-how to over 400 other people?

Vasu: Yes, that’s right. The important thing for us here at the

Barefoot College is implementing your knowledge. In a similar way, we

have had experiments with bio-gas and wind energy. When people come

to work here in Tilonia, we feel that the crazier the idea the more

welcome they are to try it out. Many people for want of a place to start,

think that their idea will never be recognised. We have had many ideas

tested here. Some have not taken off, not because of lack of opportunity,

but rather for lack of perseverance - if it’s not working you

need to find out if there is some other way of doing it.

Gradually from the 4 main initiatives of

water, health, education and livelihood, Barefoot College gradually

got involved with the physically challenged and in a big way with the

women. Further, we got involved in establishing reading room libraries

and wasteland development. In 1993, we went into computerisation of

accounts, documents, etc. What was important was to find out what the

community needed and if it could be integrated into the objectives of

the organisation.

Vicky Rossi: With regard solar technology, the Barefoot campus is

totally run on electricity from solar energy. Are you also cooking

with solar energy as I was shown some solar ovens yesterday?

Vasu: The solar cookers are more of a phenomenon from 5-6 years ago

when a man called Wolfgang Sheffler was interested in finding out if

he could install such a cooker here. Five years ago he stayed with us

for a month. His interactions with youth and women from the campus encouraged

him to return to Barefoot the following year and the year after that.

He has been able to interact with and motivate these women in such a

way that they have now formed and registered their own association that

makes these parabolised solar cookers. We have one solar cooker in the

new campus which has the capacity to cook food for about 40 people.

Then we have such cookers in all our outreach

field centres. The objective is for this association to become self-supportive

in another 3-4 years by getting orders from institutions that have residential

facilities. Self-supportive in the sense of providing a livelihood for

the women, giving them the self-belief that they can do things on their

own and forming a company that is able to make profits. Not profits

in the traditional sense, but rather profits in the form of money generated,

which - beyond the manufacture of additional solar cookers - they could

make available as wages for the women in the association. This is an

objective for the future.

Solar

cooker at Barefoot College, India

Copyright © 2007 Vicky Rossi

Vicky Rossi: You are already sharing the information and know-how

you have on solar technology with communities in, for example, Afghanistan,

Bolivia and Gambia. Is this something which is important to Barefoot,

namely, the sharing of information?

Vasu: Yes. We believe that the Barefoot approach, which we have evolved

in Tilonia, needs replication, but if it is taken up by other countries

and other communities it has to have first the endorsement of the communities

there. Over the years, we have created a process whereby we train people

only if there is strong endorsement by the local government, community

and voluntary organisations.

In most cases either Bunker Roy has gone

to different villages in these countries and talked to the rural communities,

through interpreters, to find out if they are prepared to send 2 of

their villagers to Tilonia to get trained; or there have been instances

where the village leaders have visited Tilonia as a first initiative

– like Ethiopia – and then their political leaders, their

presidents, have visited Tilonia and made a declaration that, “Yes,

we want to implement this” and later on they have sent women and

men to become Barefoot solar engineers.

By the time the solar engineers go back

to their homes they have enough skills to solar electrify their villages.

Their know-how also includes writing co-funded proposals and writing

a MOU with the government so that all their expenses are covered. Only

9% of expenses incorporated in the MOU go to cover administrative costs;

the remaining 91% is earmarked for the purchase of the solar equipment

as well for the honorarium of the solar engineers whilst they undergo

their training in Tilonia.

In the period when they get trained, the

Barefoot College tries to help either by finding out how much the government

is prepared to contribute to their expenses or by providing some funds

of our own. We feel this is a step we need to take if we want to try

to replicate our approach in a bigger way. However, once the Barefoot

solar engineers are fully trained and they return to their respective

countries, they can support themselves because they are paid a monthly

wage by the members of their communities in exchange for the services

they provide in installing, maintaining and repairing solar lighting

systems.

Vicky Rossi: Have the results been good, I mean, when the solar engineers,

who have been trained in Barefoot, have gone back to their home countries,

have they successfully implemented the knowledge they have received

here?

Vasu: Very much so. For example, we trained 6 women from Afghanistan,

who were the first women solar engineers in the whole of Afghan history.

They returned to their home country and solar electrified their own

villages. That is only one example. We feel that all the women and men,

who have gone back to their home countries, have earned credibility

within their own communities. They are even able to plan for other villages

in their areas.

Let’s take the example of Ethiopia

– we have had up until now around 40 people from Ethiopia come

to the Barefoot College and now the women have formed a Women’s

Barefoot Solar Engineers Association there. What is important is that

this initiative is seen to be a joint effort between the voluntary organisations

in that area and the Barefoot College; and that the policy-makers and

the government system also take up the idea.

Vicky Rossi: I have been quite surprised

being here that the Barefoot College is much more than a school; it

is actually a community in the sense that people are living and working

together. I was wondering then why you choose to call yourselves a

college as opposed to a community. As a second part to this question,

can you tell me if you have any cooperative initiatives in place with

other communities that are implementing sustainability and peace in

a similar way?

Vasu: Let me start by saying that the Barefoot College became prominent

because of its social and research work. Normally the paper qualification

is the point on which everybody’s value is judged in terms of

a job and remuneration; however, what is unique about the Barefoot College

is that it does not give a diploma; it does not give a certificate;

it does not have blackboards. It

has a process whereby people learn and teach.

Secondly, since the people have no resources

and since they have no alternatives, they have to acknowledge the interdependence

of one another, so they are both a teacher to one another and a learner

to one another. Thirdly, because the Barefoot College is an educational

process which is capable of mobilizing people, it’s like an open

educational process.

Fourthly, why Barefoot College? Well, because

the word gained more and more prominence when we realized – and

other people realized – that we work with the poorest of the poor.

In a way, the poorest of the poor have no chance to go to a college,

have no chance even to complete their schooling. Metaphorically, Barefoot

is a college with a difference because it is where people do voluntary

work, where people sit on the floor and take decisions, where people

have tremendous faith in decentralization and a sense of equality. They

try to see if they can internalize this process and strengthen one another,

which itself is an educational process.

Vicky Rossi: Going back to the topic

of a community, are the people who are living on the main Barefoot

College campus the teachers from the night schools, the solar technology

engineers, the people responsible for the rainwater harvesting, and

so on?

Vasu: Yes, but every one here is at the same time a teacher and a learner;

there is no “us” and “them” in the community,

for example, children get educated in the night schools and then many

of them become part-time, or full-time, volunteers with Tilonia. We

very much encourage here the idea that I can learn from somebody but

I can also try to impart my own knowledge to that person, whether this

is in terms of the solar technology, or a decision that needs to be

taken within the village, etc.

Vicky Rossi: We have touched on the subject of the empowerment

of women, but Barefoot College is also working hard to empower children.

This is done through the 150 night schools that you have in outlying

villages as well as through the Children’s Parliament. Can you

expand a little on this topic?

Vasu: In 1975 when Barefoot College started, the government handed over

to us a number of day schools because there was chronic teacher absenteeism,

which they couldn’t do anything about, and only few children were

attending. In fact, we were given 3 government day schools to run. What

we did was to use the existing curriculum, but we ran it in 2 shifts:

one was a day school and the other was a night school. That’s

how we started the night schools. Both these schools were the result

of a meeting in a village where the whole community selected 2 people

– one man and one woman – to replace the original absentee

teacher. These 2 teachers considered their work as a responsibility

rather than just a job. We continued

these schools for 3 years, but after that the government withdrew and

we continued only with the night schools.

The night schools were important because

we found that there were a lot of children in the villages of school-going

age, who grazed cattle and goats in the morning, who helped their families

to cultivate plots of land, so it was not possible for them to attend

a day school. The innovative concept of a night school appeared a little

more stimulating for the children. We realised that the timings of the

school should be according to the convenience of the children, who after

a hard day’s work could still find time for a night school. The

teachers should be from the same village where the night school is run

so that the community can put pressure on its regularity, and the administration

of the night schools should be done by a village education committee.

In this innovative concept of night schools

we realised we had to provide the children with an educational process

that had some relevance to their lives, therefore, in addition to reading,

writing and arithmetic we also provide them with information on what

a water revenue official does – in the sense of land and land

records; a little bit about veterinary science because they are involved

in animal husbandry; and information on agricultural crops and diseases

because they are subsistence farmers.

Interestingly, in the process of setting

up the night schools, we hit upon the idea of promoting their responsibilities

as citizens. We realised it would be good to include political thinking

in the curriculum, for example, information on the electoral process

and how the children could use this in the future to become responsible

grown-up citizens capable of taking part in the political process itself.

We realised that if children could take

part in a process in which they could vote every 2 years for a parliament

– together with its prime minister and cabinet – and give

them responsibilities, the monitoring of the night schools could be

done by the children themselves. This has been an innovative process

which has given us many, many insights. The desire to share in these

insights led the election commission and the government of Indian in

Delhi to give a budget of about 50,000 Indian Rupees to the Children’s

Parliament in a bid to find out what kind of voter awareness they

are able to generate.

The

Children's Parliament

at Barefoot College

Copyright © 2007 Vicky Rossi

In a sense the Children’s Parliament

is not a mock parliament. It has regular and actual powers. The Children’s

Parliament’s MPs can fire teachers if they are irregular. They

can hold to account the solar section in Tilonia if the solar electrification

is not taking place properly. All this makes them involved in a process

which aims to prepare them to be grown-up citizens. In this way the

Children’s Parliament is important.

The village education committees - in which

8-10 villagers [adults from the children’s families] become members

- assumes the responsibility for keeping simple accounts, dispersing

the honorarium of the teachers, purchasing educational materials, ensuring

that the greatest number of children possible attend the school and

mobilizing the people to understand the significance of educating the

girls. Night schools have been a pivot from which we have learnt a lot.

Vicky Rossi: Through the work of

the Barefoot College has there been any change in the attitudes of

people towards the caste system?

Vasu: In the night schools we have found that most of the teachers belong

to the lower castes but the children who attend belong to all castes.

In the classroom, the children all sit together, drink together, eat

together, etc. We try to address the whole question of caste through

puppet shows, interactions and role models.

For example, most of the workers here in

the Barefoot College, who belong to the lower castes, have become very

senior persons in Tilonia and have tremendous credibility in the villages.

They have become role models that people can look up to. Some of the

indicators of positive change include the fact that many villagers are

no longer marrying off their daughters at a young age – child

marriage is a big problem here; they are seeing to it that the children

receive sufficient education; and they are making sure that they don’t

have highly expensive weddings; etc. This change in attitude has to

come from the people themselves.

Vicky Rossi: As you know, immediately prior to coming here to the

Barefoot College, I took part on the Gandhi Legacy Tour (1), led by

Arun Gandhi (2), during which we visited various sites related to

Mahatma Gandhi as well as organizations that are running their projects

in accordance with Gandhian principles. It seems to me that the Barefoot

College is very similar in that respect. There is also this emphasis

here on the importance of the villages, which is a concept that Gandhi

very much emphasized. I was wondering if it is a conscious decision

to integrate Gandhian principles in the running of the Barefoot College.

Vasu: When the organisation was founded, the Barefoot College here in

Tilonia felt that it could implement many of the things which Gandhiji

(3) said because they are very simple. You don’t have to call

yourself Gandhian, just be the change that you want to see in the

world as he always said. As long as you are trying out what he

said, trying to put into practise what he said, that’s what’s

important. Gandhiji talked about rainwater harvesting 110 years ago

in his Tolstoy Farm in Durban. If the Barefoot College is doing that,

we are only trying to emphasize what he was saying. At the same time

we do not call ourselves Gandhians because we do not have to. What is

more important to us is to implement his ideas, which are so simple

and so low cost. We don’t mind if we are called Gandhians, but

for us it is a way of life – that’s what’s important.

Vicky Rossi: In the talk you gave earlier today, you mentioned that

many of the conflicts around the world are the result of greed over

natural resources, for example you mentioned diamonds in Africa and

oil in other countries. Would you say, therefore, that the Barefoot

College is promoting peace in the sense that it is sharing know-how

in solar technology, which in turn provides independence from other

energy resources that are often points of conflict? Do you see the

Barefoot College as promoting peace and not just sustainability?

Vasu: The day we started living as a community, we created a code of

ethics which includes 3 important points:

- firstly, the moment any volunteer uses

force with another person, he/she is out of the community;

- secondly, in all our initiatives we

will see to it that the laws of the land are followed – we will

not take the law of the land into our own hands, however, we will

use that law to the benefit of the poor, who have been oppressed;

- thirdly, the women’s groups here

have been working to reduce violence in the homes – violence

against women.

Through this code of ethics, we actively

check to see if we are practising nonviolence in our own lives. When

you are living in a society which practises violence, but you yourself

are trying to implement nonviolence it certainly has a rub-on effect.

It rubs on to the children and has an effect on so many other things

too.

Our own “non-negotiables”,

which we don’t compromise on, have instilled in us a faith in

sorting out problems without using violence.

*This transcript represents an

accurate but non-verbatim representation of the original interview.

I would like to thank all those who made my trip to India possible through

their moral and financial support.

For further information, please contact:

S. Srinivasan (Vasu)

The Barefoot College

Village Tilonia, via Madanganj,

District Ajmer

Rajasthan 305816,

INDIA

Tel: +91 (0)1463- 288206

FAX +91 (0)1463-288208

Email: barefootvasu@gmail.com

Website: www.barefootcollege.org

Footnotes

1. Global

Exchange, Gandhi Legacy Tour

2. Gandhi Institute of Nonviolence

3. “Gandhiji” is a term of respect and endearment for Mahatma

Gandhi.

Links

“Fighting

Poverty in India”, BBC News, 27 December 2001

The

Global Rain Water Harvesting Collective,

UN Partnerships for Sustainable Development

“Barefoot

College award will train village women SUCCESS STORY”, peopleandplanet.net,

27 May 2003

“Poor

and female but smart”, GoodNewsIndia, 21 October 2003

Best

Practices of Non-Violent Conflict Resolution in and out of School,

UNESCO (PDF format)

“Children’s

parliament boosts India health”, BBC News, 26 August 2002

“Bal

Sansads: Members of Parliament at 11”, by Lalitha Sridhar,

InfoChange India, May 2004

Agfund

Prize 2001

“Indians

win two of the four ‘Green Oscars’”, rediff.com

,19 June 2003

Tyler

Prize 2001

Copyright © TFF &

Rossi 2007

Tell a friend about this column/interview by Vicky

Rossi

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

Get

free articles & updates

|